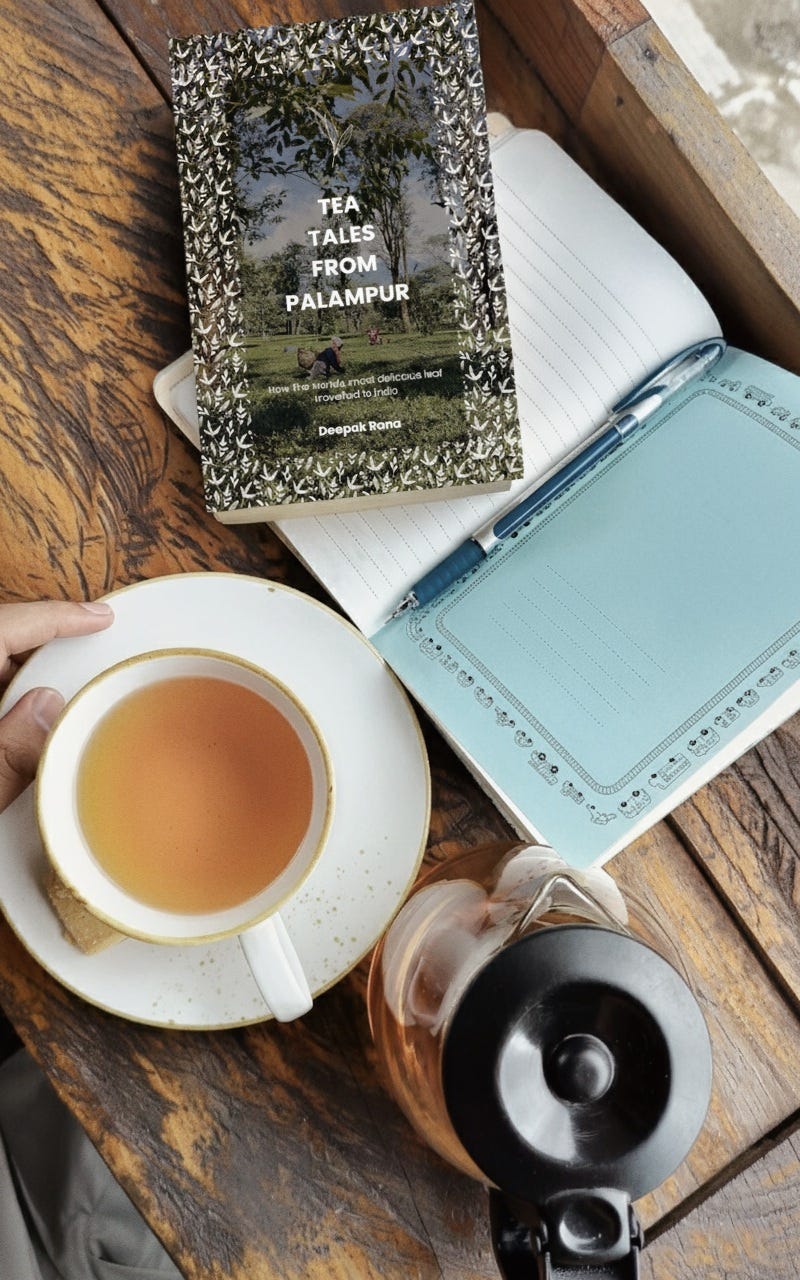

Read my new book here!

Hi there,

I know I’ve been away for a little while, and some of you actually wrote to ask if everything was all right. Yes, everything is all right — it has simply been a season of busyness (not necessarily business). My new book, Tea Tales from Palampur, has just been released, and in those final weeks before publication I found myself completely wrapped up in edits, emails, promotions, and that strange mix of excitement and nervousness that comes with sending a book out into the world. It’s been quite an experience, but the mostly good kind.

I’ve missed writing to you, and I didn’t want to return empty-handed. So today, I’m sharing with you a small gift: a sample chapter from Tea Tales from Palampur. It’s one of my favourite pieces from the collection — simple but full of the quiet warmth that tea, hills, and stories bring into our lives. I hope it finds you in a moment of stillness, and that it carries you, even briefly, to the slopes and silence of Palampur. Amen!

Sample Chapter

Zen Way of Drinking Tea

Like many concepts in Eastern philosophy, “Zen” has no precise English equivalent. Derived from the Chinese Ch’an and ultimately from the Sanskrit Dhyana, it is often translated as “meditation,” though that word scarcely captures its meaning. What is fascinating is how Dhyana travelled from India to China, then to Japan as Zen, and finally returned to us, only for us to embrace it again as Zen rather than our own Dhyana.

Perhaps that is who we are: we often find the familiar too ordinary and fall in love with it only after it has travelled the world and returned with an exotic name. Yet, at its heart, the meaning remains the same. In India, Dhyana signifies a state of direct communion with reality itself, and in Japan, Zen carries this same spirit: not a retreat from the world but a deep presence within it. It is found not in isolation but in the ordinariness of life, in chopping wood, cooking rice, or cleaning the floor. If we must translate it at all, “enlightenment” comes closest, though Zen is both the light and the path towards it.

How does tea relate to the idea? Well, an ancient poet once wrote:

The first cup moistens my lips and throat, the second cup breaks my loneliness, the third cup searches my inmost being… The fourth cup raises a slight perspiration— all the wrongs of life pass away through my pores. At the fifth cup, I am purified; the sixth cup calls me to the realms of the Immortals. The seventh cup— ah, but I could take no more! I only feel the breath of cool wind that rises in my sleeves. Where is Heaven? Let me ride on this sweet breeze and waft away thither.

Such were the feelings that became associated with tea-drinking. It was much more than a drink made from dried leaves, for a Zen master could say: “Mark well that the taste of Zen (Ch’an) and the taste of the tea (Cha) are the same.”

In the Zen tea ceremony, we find the Zen philosophy in its most peaceful aspect, expressed through the slightest spiritual gesture, and utter deficiency of things. It was an expression of the natural order— the harmony of belonging and its basic principles were an insistence on the transience of nature, of her unending changes, mercy, her avoidance of variety, her avoidance of flashiness, and lastly the indefinable quality called yugen, which is described as ‘the subtle, as opposed to the obvious.’

Can we recreate that rich experience in our tea ceremony? Well… we can certainly try. I did.

***

The tea leaves that I had brought from the estate, there were a few of them left. I made the green tea just as I had described in the previous chapter, packed it carefully in a small flask, and began walking towards the river.

I walked close to Hideout Cafe. I think it is better that the cafe remains a hideout, and nobody ever finds it. Because right next to it lies a big dump of garbage, an eyesore that even the generous Dhauladhar sight cannot redeem. The recycling processing unit nearby hums constantly, and the smell of rotting waste drifts across the bridge where a few travellers sit, sipping coffee and pretending not to notice. Clearly not the place you would want to be.

I kept walking upstream, following the sound of the river until the air grew clean again. The smell disappeared, replaced by the freshness of pine trees and water. I found a flat rock, sat down, and dipped my feet into the cold water. The river flowed around my ankles as I poured myself a cup of tea. The sun was setting right in front of me— soft gold scattering across the ripples, steam rising gently from the flask. For a moment, which felt like eternity, there was nothing else I needed.

***

There are two ways to have a tea experience. We have these two choices every time, and they are not just about the tea. One is to immerse yourself in the act of drinking tea, relishing every drop of it: its taste, aroma and sensations that it stirs in you. The other is by letting your mind wander to the past or future, and missing out on the experience of tea completely. The first is what mindfulness asks us to do, something I experienced on that day at the river; the second is what most of us do most of the time.

It’s easy to tell which way is better. But then, we cannot keep obsessing over tea, right? That will defeat the whole purpose.

Let’s go back a few moments. If while washing the dishes you think only of the cup of tea that awaits you, thus hurrying to get the dishes out of the way as if they were a nuisance, then you are not washing the dishes to wash the dishes. In other words, you are not being mindful.

What’s more, you are not alive during the time you are washing the dishes. In fact, you are completely incapable of realising the miracle of life while standing at the sink. If you can’t wash the dishes, the chances are you won’t be able to drink your tea either. While drinking the cup of tea, you will only be thinking of other things, barely aware of the cup in your hands. Thus, you are sucked away into the future, and you are incapable of actually living one minute of life.

This is what we mean when we use the word mindfulness. It is the acceptance of the present experience. It is opening to (or receiving) the present moment, pleasant or unpleasant, just as it is, without either clinging to it or rejecting it. Simply experiencing things as they come. Without worrying about our thoughts or letting them spoil every other experience that we have.

The act of drinking tea can be therapeutic: it depends on how well we do it.